If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.

Toni Morrison

Who are we writing for, anyway?

Since Toni Morrison died in 2019, I have encountered many times the above comment attributed to her. And every time I think of it, something about it makes me uncomfortable.

It sounds inspiring, doesn’t it? A Nobel-Prize-winning author inviting us all to write the book that we want to read. We sense the underlying assumption that we, and only we, could write that book. We are nudged to attention by the imperative that if we believe that something in our world has been as yet unsaid and needs saying, we are obligated to take up a pen, or sit at a keyboard, and say it.

Across the world of online writing advice to would-be novelists, Morrison’s comment has been distilled down to, Write the book you want to read. Admittedly the imperative has some credence, since if we want to read the book that we write, chances are others out there in the book-reading population will want to read it, too. Still, something troubles me about this notion.

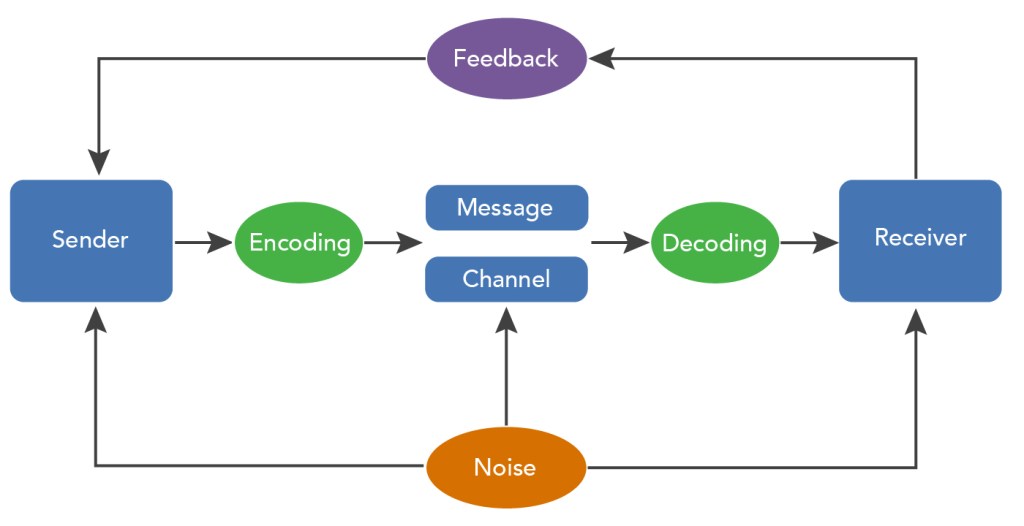

Writing is communication. It can be communication with oneself, yes. Most often, however, communication involves others. It requires senders and receivers; speakers and listeners. A writer and readers. As communication, writing is a social act. It is a way of bringing people together around a set of ideas. It is a way of teaching, entertaining, encouraging, warning, persuading, and empathizing.

In one of my previous posts, “How Much Should We Really Think about Audience?” I questioned the emphasis that composition pedagogy places on our awareness of a reading audience. I suggested that determining what kind of audience we should be imagining as we write is not as clear-cut as we are taught to believe. Because of that, I proposed, we should consider ourselves to be our primary audience.

I’m not backing down from that position. At the same time, though, I don’t think we should, or do, write strictly for ourselves.

Write the book you want to read. Of course I want to read my own writing. I take pleasure, at least sometimes, in seeing my words on the page and appreciating the amount of work I have put into getting them there. But I value the thinking and writing of others. I want to read books written by people other than myself. I want to absorb ideas that are not my own and learn from them.

Of course I write what I want to read, or more accurately I want to read what I write. But the idea that I should consider myself to be the most important reader of what I write and that I should create a text to suit myself alone is frighteningly limiting, isn’t it? Doesn’t it lead us into a narcissistic endless loop in which we are exposed only to our own ideas? Isn’t it like placing ourselves in a kind of intellectual deprivation tank?

Many of the writers that I know do write to please themselves. But they are also fueled by positive feedback from others. They desire an audience for their writing so much that they are willing to send their work out to publishers and wait months or longer to receive what is in most cases a cursory rejection—all for the chance to reach an audience of readers. When their work is accepted by publishers, they are willing to receive minimal or no compensation for the opportunity to place their work before a reading public. Writers write for others. And they should.

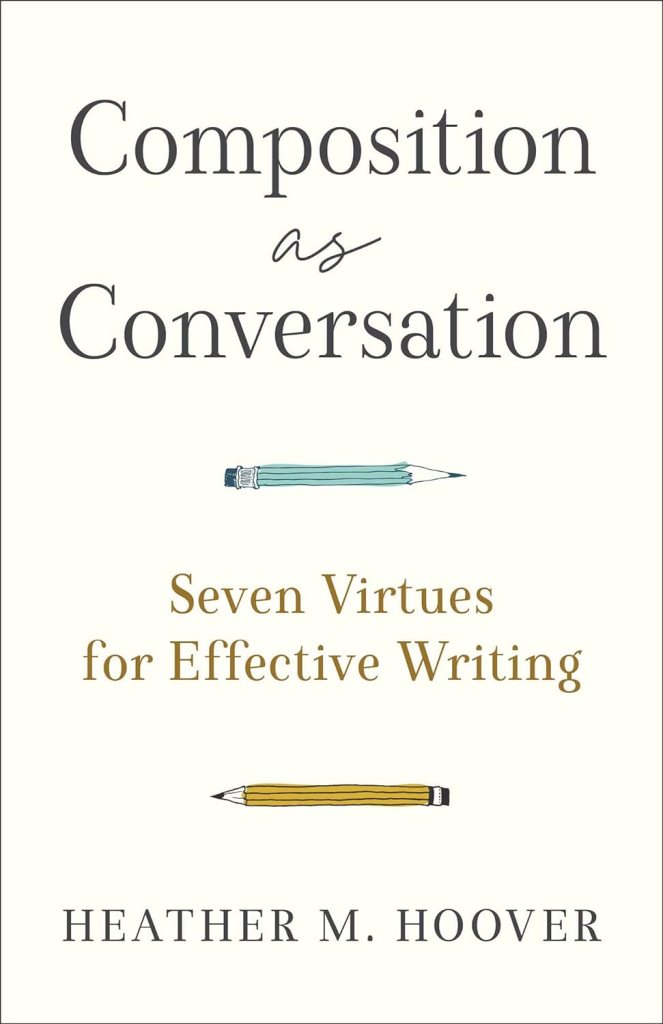

As I was writing this post and pushing myself to try to understand why Morrison’s comment causes me such discomfort, I received a package in my office mailbox. When I opened it, I found Heather Hoover’s new book Composition as Conversation. It arrived as if to clear up the tension I was experiencing and to answer the questions I asked above. The premise of the book is that writers should regard their writing as part of an empathetic, respectful conversation with others. By teaching college composition as conversation, Hoover has inspired her students to take interest and pride in their work and to consider it an important form of interaction with others. By approaching their work in the way that she suggests, writers may, and probably will, write something that they themselves want to read. But that shouldn’t always be their sole aim.

Writing is great for the writer. But at its best, writing is planned, designed, refined, and offered up for a reader.

Leave a comment