My sister drives confidently over the rollercoaster hills and hairpin curves along the road through Cameron. She’s a born West Virginian. The town clings to a slope of the Allegheny range’s shamrock green mountains. Its thousand or so inhabitants shelter themselves in humble houses perched on rough ridges or squatting in ravines. We are here to visit our father’s birthplace.

Linda, my sister, is seventy. I am sixty-five. We met just four months ago.

Something was missing for both of us, I suppose. The reason we both decided to have our DNA analyzed by Ancestry — we were looking for what would fill an emptiness we had lived with for so many years. We felt a longing for a voice — strange yet familiar — to break an overlong silence. We had been waiting for someone to arrive, to see a face we would recognize — one we had each been looking for all along.

The DNA test revealed that Linda and I have the same biological father. For the first twelve years of my life, I knew him as Daddy, the quiet man who inhabited my childhood. Then he died, after which he became a mere myth — someone I invented and reinvented over the years from the scant framework of memory.

Linda never knew him. She grew up thinking another man was her father. The man who raised her, supported her, and saw her into adulthood after her mother abandoned her. The man whose three other children, her siblings, comprised her family. But something was not quite right. Linda knew that. She was different somehow from the others.

Stories of identical twins separated at birth who find each other as adults fascinate me. Sometimes, they discover that they have similar careers, identical likes and interests, pets with the same name, or the same make of car. They describe their first encounter with each other as like looking in a mirror.

As half-sisters, Linda and I are a 25% DNA match. Far from identical twins, we nevertheless resemble each other, share likes and dislikes, and have similar interests. But over the years before we met, we maintained different lifestyles and pursued different careers. And we lived a long time before finding each other.

We endured the clumsiness of meeting each other for the first time, each of us seeing a glimmer of herself in the other, halted by the strangeness of the first encounter but driven by an undeniable bond. Then we decided that, beyond getting acquainted with each other, we needed to get to know our father. Through him, we thought, we would learn to know and love each other. Though he has been long dead, we needed to find him.

Linda traveled from her home in Pennsylvania, and I from mine in Michigan, to West Virginia, to learn what we could about our father’s life.

Cameron

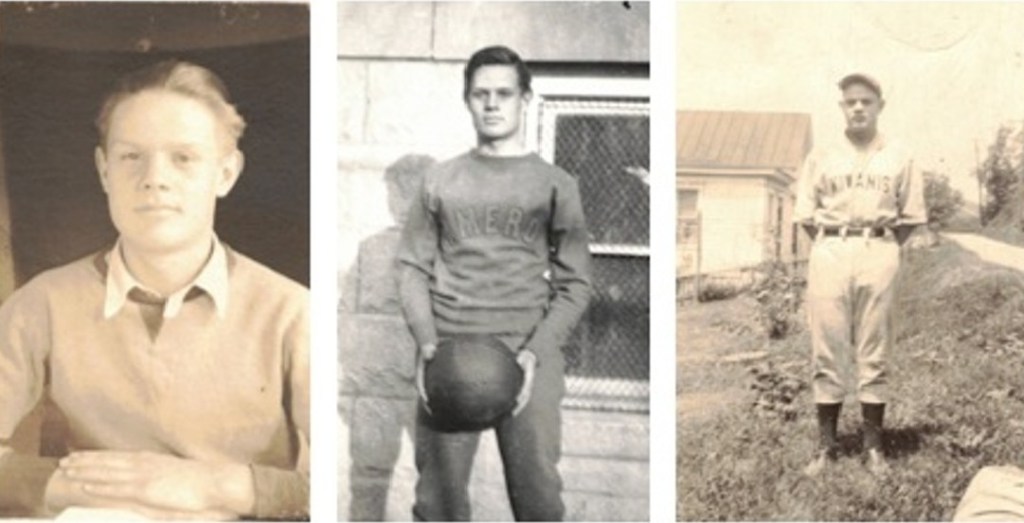

Our quest takes us first to Cameron, where our father, George Russell Wilson, was born in 1915, and where he attended school. We visit the cemetery where our grandparents and a few other family members are buried, high on a ridge overlooking the undulating hills of what was his first home.

No level ground anywhere. Even the cemetery’s graves are dug into hillsides, the headstones lopsided, some leaning one against another.

“Let’s get a shovel and level up Aunt Imogene’s headstone,” Linda suggests.

I am struck by her willingness to take care, as best she can, of these silent, faceless strangers—these patches of earth—who are her newfound family.

“Now, how would that look?” I ask. “Two old ladies traipsing through a cemetery with a shovel? We might get arrested for attempted grave robbing!”

I am the careful sister, we note. Linda is the risk-taker.

West Liberty and Wheeling

We descend from the ridge, take to the highway, and arrive within a few minutes at West Liberty, where the Wilson family lived during the late 1930s. A university town with a small resident population, this is where our father first met Linda’s mother, Joanna.

Weaving through streets that here and there plunge suddenly down toward a hollow, we find the neighborhood where the Wilsons and Joanna’s family lived. Frame shanties snugged against the sidewalk; these are the dwellings of hill people who managed to keep themselves just one step beyond poverty.

“That’s my grandmother’s house there,” Linda points out. She recalls spending time there as a child. On the other side of the street and a few doors down, the Wilson house stands.

We try to imagine George and Joanna — how their families must have known each other as neighbors. How the two of them grew to adulthood together and, in 1940, decided to marry.

Linda looks solemn as we travel to Wheeling, where the newly married couple lived until George joined the Army in 1942 and spent four years during World War II in Germany. We find the house where they lived, the place Joanna stayed while George was overseas.

For me, finding this place shows me an interesting bit of my father’s history that took place years before he met and married my mother. But how is this discovery affecting Linda? How is she coping with her knowledge that her mother was married to George before she married the man Linda knew as her father? We are chatting as we drive, but are we saying anything meaningful? Or are we avoiding making meaning from all this?

We are awakening ghosts — shadows of a newly married couple enduring wartime. Two young people, George and Joanna, coping with their circumstances and making decisions about their lives, for better or worse. Strangers to both of us, yes. But Linda knew her mother. And I knew my (our) father. How do we make sense of what we are experiencing together? Will it draw us close to each other? Or will it create tension between us?

Wellsburg

We head to Wellsburg, where George lived and worked as a restaurant manager for G.C. Murphy Company after the war. Researching available records allowed me to discover that when George was discharged from the Army, he returned home to Wheeling, after which he and Joanna quickly divorced and, shortly after, Joanna married someone else.

I surmise from my research that George returned home to find his wife pregnant and living with another man. Soon after the divorce, Joanna married Leland, the man Linda would know as her father. Within a few months, Joanna gave birth to her first child, a daughter named Constance. George moved to Wellsburg to start a new life alone.

In Wellsburg, we find the G.C. Murphy Company building where our father was a restaurant manager. It now serves the community as a historical museum. How appropriate, we thought. Linda and I embrace it as a museum to our father’s, and our own, history. George spent several years there as a single man, building a good reputation with the company for which he would work until his death in 1972.

Cumberland, Maryland

During the early 1950s, our father’s history blurs. Sometime between 1950 and ’55, Murphy’s transferred him from Wellsburg to Cumberland, Maryland. There he met Lydia, my mother.

Early in 1954, however, he reunited with Joanna, and Linda was conceived. We don’t know if they saw each other frequently during the years following their divorce or if they were together only once—a time in March of 1954 that led to Linda’s birth in New Martinsville, West Virginia, the following December.

Was this an ongoing love affair between our father and a married woman, Linda’s mother, or was it a chance encounter between them during which they succumbed, however briefly, to their unresolved attraction?

So much of life is unchronicled. So much lies beyond written records — census reports, marriage certificates, birth records, and obituaries. The details of our father’s life in the early ’50s and the circumstances that led to my sister’s birth may be forever unknowable.

In 1955, George married Lydia. In 1960, I was born. I lived as an only child with my parents until my father died.

We leave Wellsburg and head east toward Cumberland, Maryland, my hometown, the last destination of our road trip. We’re approaching my territory, so now I do the driving. Linda argues with me about which route to take.

“I’m the big sister,” she says. “You have to do as I say. Take Route 70 and go southeast. It’ll get us there much quicker.”

“No,” I say, “I’m going my way. The way I know.”

I want to take Route 79 South so I can access I-68 East from Morgantown to Cumberland. It’s a familiar road, one I drove many times when I lived in Maryland.

“Come on,” she says. “Go a new way. Don’t you have any spirit of adventure?”

No spirit of adventure? I have embarked on a trip with a virtual stranger I met a few months ago on Ancestry. I didn’t know when we started out what kind of psychological stress this quest for our father might cause. I didn’t know what the emotional outcome of this trip might be. Don’t I have any spirit of adventure?

“I guess not,” I reply, turning onto Route 79.

When we get to Cumberland, I drive to the cemetery where our father is buried. I haven’t been there in years, so I have trouble finding his grave.

During our search, Linda seems distracted.

“Who are we looking for?” she asks.

“George Wilson,” I say. “We’re looking for George R. Wilson.”

After wandering over section after section of the cemetery, we find it. When I see the gravestone, I point to it.

“Linda, this is your biological father.”

I say it as if I’m introducing her to a person. Gesturing toward the gravestone as if it were her father’s face.

She looks at it for a few moments.

“Well, I’m finally here,” she says, addressing the flat marker that bears his name. “I finally caught up with you. You can’t hide me anymore.”

I’m surprised by her words and by the anger with which they are spoken. The impulse to apologize overwhelms me. I want to say I’m sorry to Linda, because she never knew her birth father. I want to ask my father for forgiveness for bringing this secret to light. My mother, too, for I’m sure she would be angry at me for doing this. I stand there saying I’m sorry to a plot of ground.

Linda and I argued for a few minutes about whether or not he knew about her. Whether he knew but never attempted to meet her, know her, or be a father to her. She says he had to have known. I feel obligated to defend him. Maybe he didn’t, I say. We can’t be sure.

Finally, she reaches down and lays her hand on the gravestone for a few moments.

“It’s warm,” she says.

We walk away from the grave together in silence.

. . . . .

I drove alone from Cumberland back to my home in Michigan. Our road trip was complete, and Linda and I parted, but only temporarily.

For all the losses we have suffered by not having our father in our lives, we have gained each other. We have found what was missing, the thing for which we had both searched for so long.

She and I are committed to the hard, complicated work of being sisters who found each other late in our lives.

Linda says I’m not an only child anymore; I’ll just have to get used to having a sibling.

I guess I have to do as my big sister says.

Cover Photo: Generated by Gemini

Leave a comment