Dear writer:

In a few moments, I’m going to ask you to close your eyes.

Sometimes, the best way to be successful at doing something is to not do it for a while.

Imagine you’re tackling a persnickety home maintenance task, for instance. You’re trying to fix a dishwasher that refuses to wash or figure out why your garage door opener is lifting the door on its own at night. When things aren’t going well or your patience has reached its end, it may be best to step away for a while.

Giving yourself time and distance from a problem you can’t seem to solve is a good idea.

The concept of meditation contradicts what is generally demanded of us: productivity, action, busy-ness. The imposition of our will on whatever is in our way. We must climb over stumbling blocks and demolish the walls between us and what we want.

I get it. Productivity is good. Action keeps our blood flowing. Doing makes the world go round.

I started meditating when I was sixteen. My Aunt Susie, a proselytizing New Age enthusiast, insisted that I learn transcendental meditation. I brought the required offering of fruit and flowers to my initiation session, knelt before a picture of Guru Dev, received my mantra, and emerged from the incense-imbued training room with a useful technique — one that I have used throughout my life to cope with anxiety, depression, and other ills.

Since then, I’ve learned that meditating doesn’t require all of those trappings. It doesn’t even require training. No mantra needed. Meditation is a deliberate turn inward, into oneself, resulting in a cessation of activity that would feel more natural to us if we were not so indoctrinated in the importance of perpetual action.

Writing can be frustrating. Sometimes a conundrum. Sometimes seemingly a dead end. Like those household tasks that may best us for a while, writing may seem at times too difficult. We may say we have a block. We may feel we can no longer find our groove.

Sometimes the best way to be successful at doing something is to not do it for a while.

One of my own writing struggles

Many years ago, when I started taking my writing seriously, I struggled with the question, Who am I?

I know, I know. An age-old universal question.

But I struggled to understand who I was as the voice of my writing. When I wrote, who was it who addressed the reader? As a nonfiction writer, I feel obligated to say that it’s I, Georgia Kreiger, who speaks in my writing. I have to write authentically as myself. But what does that mean?

I struggled with which details about myself to include in my writing, how to convey my credibility, how to use diction to put myself on the page. What picture of myself should I create? And how?

As a college writing instructor, I was accustomed to advising my students that, as they approach a writing assignment, they must ask, Who are my readers? And, What is my purpose in writing to them? But I didn’t always ask them to consider, Who am I when I’m writing to them? I didn’t think about how this question might facilitate their writing.

Then I read Carl Klaus’s book The Made-up Self: Impersonation in the Personal Essay. In it, he explains that when nonfiction writers formulate their messages to readers, they are the shapers of their texts, but they are also shaped by what they write. As we write, we construct ourselves as the speakers of our messages. Klaus notes,

An essay might appear to be a stroll through someone’s mazy mind, but [it is] a mind that is always in control of itself no matter how wayward it may seem to be.

The control Klaus refers to consists of the choices writers make about how to present themselves to readers. He tells us that the I that speaks in our writing is a construction, and we are its builder.

How do we lead readers to feel that they know us?

We create a persona — a metaphor that clothes the abstraction that we are in qualities that make us knowable.

I thought I understood all that. But I was paralyzed by my lack of know-how to take those qualities and wrap them in a metaphor.

Meditation was the answer

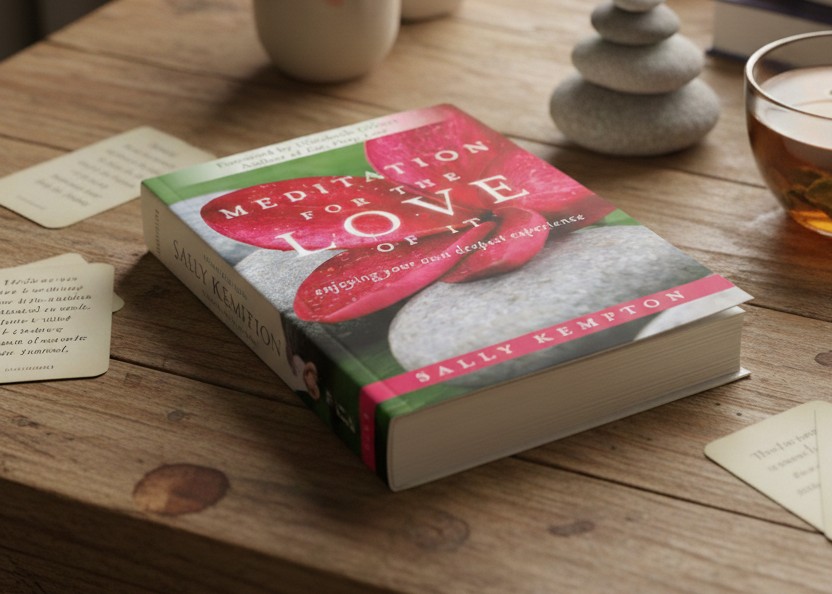

A few years ago, a friend gave me Sally Kempton’s book Meditation for the Love of It: Enjoying Your Own Deepest Experience. Kempton guides readers through a series of meditative exercises that allow us to turn inward to discover what is within us. The fourth meditation in her book caught my attention. It read, simply,

See if you can station yourself as the observing witness of your body, seen from all sides.

Could visualizing myself as an outside observer help me find my writing persona?

I decided to try it.

I closed my eyes. I looked into the rich darkness that floated behind my eyes. I let myself sink inward, away from the external world. I waited there for a few moments, without expectation.

See if you can station yourself as the observing witness of your body, seen from all sides.

I let those instructions repeat in my mind.

Then I saw a circle in the midst of the darkness.

My line of vision seemed to be positioned on a dolly, like the kind used by cameramen to circle a person or object to provide a 360-degree view. My view traveled around the circle as an image appeared.

Within the circle, a bear.

I saw myself there, a bear sitting on its haunches, eyes closed, as if it, itself, were meditating. As my view traveled around it, I saw that it was big, ungraceful, hunched. Dull-furred. Quiet.

A bear? I thought. This is what my mind shows me? I’m a bear? Not a graceful gazelle or a lithe leopard? Not a vibrantly colored fiery-throated hummingbird?

A big, clumsy bear?

But then, as I stared into that darkness in my mind and studied the bear, I understood. It appeared strong, yet gentle. Fierce and unstoppable, yet nurturing and protective. I thought about mythical bears.

All right, all right. I get it.

But how could I explore my bear persona in my writing?

After the meditation, I turned to my keyboard and typed this rough draft of a poem.

………..

Ursa of the Suburbs

First seen scuffling among the cans on garbage day,

nuisance in the neighborhood, a big triangle lumbers,

thrashes their trash — the sucked bones and wet

plastic wrap of their lives — paws out some wise tale,

some grace.

Next noted in a backyard bronzing in the late-summer sun,

heavy-haunched,

and later, robbing the birds and young boys’

sweet stashes.

Viewed by her child, the one she bore

through the thick of things, a disturbance in the tranquil

trees ahead

like the one that inspired Zeus to hurl

his major and minor problems

to the sky

When the time arrives, a woman becomes a bear.

And watching,

the neighbors shake their heads,

saying,

If we keep our distance, she won’t do any harm.

……….

My mind knew what it was doing. I was a bear — a middle-aged woman lumbering through her world, digging and scuffling to find her usefulness. Overlooked, until she caused trouble. Misunderstood.

Dear writer, try this:

Whether you are struggling to find your voice, or to recognize and speak to your audience — those readers who are out there waiting for your message — meditation can help.

Part of the writing process is not writing. It’s turning inward and allowing what’s inside us to reveal itself. It’s inviting the mind into stillness and fostering focus.

Meditation can calm our frustration with our inability to get our words, and ourselves, on the page. By letting go, we experience the abundance in our minds.

So, try it.

1. Close your eyes.

2. Observe what is there in the darkness behind your eyes.

3. Let all distractions — your slight headache, perhaps, or your anxiety about writing, your need to get ready for an appointment later, or your anticipation of lunch — let all that recede from your consciousness and gradually disappear.

4. Sit with your intention to write. Only that.

5. Expect nothing. Watch. See what your quieted mind shows you.

Then write.

……….

Cover Image: AI-generated by Gemini

Leave a comment