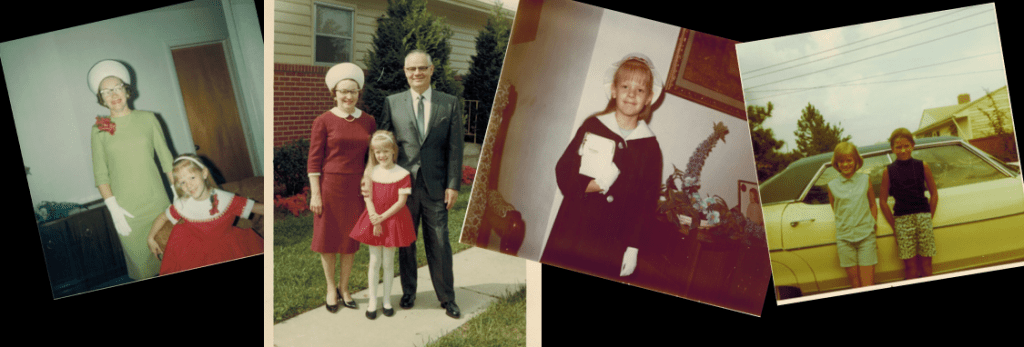

In this post, I continue my exploration of using childhood photos as a catalyst to writing memoir by experimenting with analyzing some of my own childhood photos.

The first task when faced with stacks of family photos that are largely alike in their presentation of a single person or people, most often facing the camera and often smiling, is to select photos that seem likely objects of analysis.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes provides a method for identifying such photographs. Certain photos will attract us, Barthes suggests, because they will stir “an internal agitation, an excitement, a certain labor too, the pressure of the unspeakable which wants to be spoken.” Something about such photos disturbs us or demands our attention, he explains, due perhaps to the “co-presence of two discontinuous elements” that create “a kind of duality.” It is the element within the photo that compels us to look.

After my mother died a few years ago, I inherited the box of family photos that she’d kept in her bedroom closet. To say that my relationship with my mother was troubled is a rank understatement, but let’s leave it at that. Bringing this box of photos into my home was painful. I was allowing whispers from the past that I had long repressed into a space that I had worked for years to make safe for myself. I decided that the best way to cope with this barrage of unpleasant memories was to approach the photos as an analyst, looking at them as someone studying the family rather than as one damaged by it.

I found photos that meet Barthes’ criteria for analysis. Two of them I chose to analyze. One was taken of me when I was an infant. It is an example of a photo that calls for speculation, since I do not remember anything about the occasion of its taking. The second one is a photo of a remembered occasion. Not only do I remember the occasion on which it was taken, but I remembered the photo itself, and looked for it specifically when I started searching through my mother’s box.

Photo that Calls for Speculation

I know that this is a photo of me, and I think that I might be close to one year old. I assume from stories I have been told about my early life that the street behind me is Magruder Street, in Cumberland, Maryland, where my parents lived when I was born. I do not know who the photographer was nor what prompted the taking of the picture. I see just a sliver of what I assume to be the photographer’s shadow in the lower right of the picture.

This photo contains an instance of what Barthes refers to as “duality.” It is the element that attracts my attention and raises my curiosity. What one might expect to the be subject and focal point of the picture, the small child, appears at the bottom of the image and is partially cut off at the photo’s border. Something with the child that appears to be a stuffed toy or perhaps a blanket is almost completely cut off. The child appears a little off center at the bottom of the image, not where the subject of an image is normally positioned. And the child has been placed between the sidewalk and curb, next to the street, on a segment of grass. That seems an odd place to position a child for a photo.

The neighborhood in which the photo was taken appears to be the real subject of the photo, since it is positioned centrally in the picture as the focal point. The houses in the distance and street itself seem to be the photographer’s subject.

Based on my observation of my other childhood photos, the construction of this image makes sense. Photos of me as a child placed in front of the family’s new car, or the new custom-made draperies on the windows, or seated in a new chair purchased for the living room are common. I speculate that in these cases the child is included in the image as a reason or a justification for the photographer to snap the picture, while the real subject—what the photographer wants its intended viewers to see—is evidence of the family’s relative prosperity. I recall that my mother spoke proudly of her house on Magruder Street—the first house that she and my father owned. My mother grew up in a large, poor family in Western Maryland. For her the house on Magruder Street was a step up in socioeconomic status, and something worth recording and documenting for others to observe.

Photo of a Remembered Occasion

In this photo I am six years old. My father and I are alone in the backyard. He has brought his camera outside with him because only one exposure is left on the roll of film, and he wants to finish the roll and take it to the drug store to have it developed. We have recently moved from McKeesport, Pennsylvania, to this house in a subdivision of suburban Richmond, Virginia. I am in first grade, in love with school, learning to read, and glad to be able to escape our troubled home to the ordered, reliable setting of the first-grade class.

The tension in this photo, the contradiction that makes it attractive to me, is that in order to take the picture my father had to be standing in our neighbors’ yard. I was not allowed to stray into someone else’s yard without permission, and my father didn’t like people coming into his yard. And he didn’t like these particular neighbors. The father of the family was an alcoholic, and often violent when drunk. I can recall episodes of the neighbors fighting that contrasted with the more quiet family drama that was going on in our house. Why my father was in the neighbors’ yard is a mystery to me. Why he took the photo from a position below me is also puzzling. He would have to have been sitting on the ground, or maybe he was down on one knee. And why was I placed at the very corner of our yard, where our yard met the neighboring properties?

Analyzing family photographs is a worthwhile prewriting exercise, and it may help us to organize and make sense of our stories of the past. Our childhood photos may provide us with subjects for our writing, or they may help us to give greater substance to what may be fragmented or partly repressed memories.

Leave a comment